Your cart is currently empty!

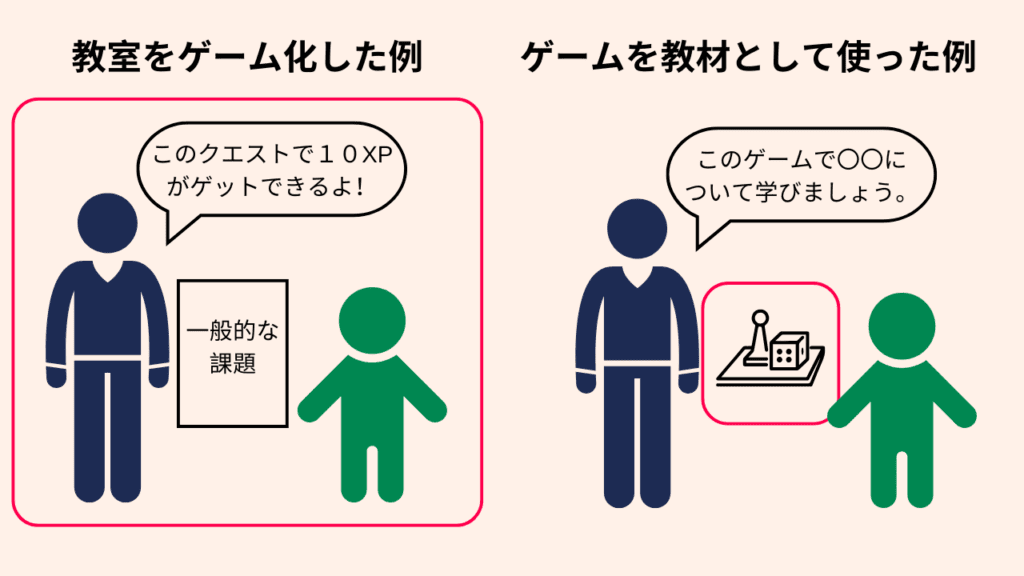

ゲーミフィケーションではなく、「遊び心」を導入しましょう

English version follows Japanese!

はじめに

教育の現場では、いまだに「ゲーミフィケーション」という言葉がバズワードのように使われています。これは、おそらく授業内容や指導法、教育そのものを根本から見直すよりも、ゲーミフィケーションを導入する方が手軽だからでしょう。

実際、私自身も2012年にはその可能性に惹かれ、授業でゲーミフィケーションを試してみました(York, 2012)。学生にいくつかのタスクから選ばせ、自分に合った学習方法で進めてもらうという方法です。しかし結果として、学生のモチベーションが高まるというより、最も簡単なタスクばかりを選んで取り組むようになりました。つまり、挑戦的な課題には手を出さなかったのです。

このような行動は、外発的な報酬の弊害として知られています(橋口, 1982)。報酬を失いたくないという気持ちが強まると、人は失敗のリスクを避けようとし、安全で確実に報酬が得られるシンプルなタスクを選ぶ傾向があります。

このように、ゲーミフィケーションの導入は一見効果的に思えるものの、実際には学習者の行動に予期せぬ影響を与えることがあります。この記事ではゲーミフィケーションではなく「遊び心」のある教育が必要だと伝えたいです。そして、いくつかの実際例も紹介します。

Duolingo

教育現場を訪れる前に、ゲーミフィケーションの代表的なアプリとしてまず挙げられるのがDuolingoでしょう。「ゲーム的要素を取り入れたサービス」として広く紹介されています。しかし、本当にこれらは「ゲーム」と呼べるのでしょうか?また、こうしたサービスを教育に導入することが、本当に学びの質を向上させると言えるのでしょうか?

近年、Duolingoは大きな批判を浴びています。その背景には、ゲーミフィケーションの仕組みそのものがあると私は考えています。ゲーミフィケーションのraison d’être(存在理由)は、ユーザーの行動を操作・制御することであり、主に以下のような目的で用いられているでしょう。

- 集客力を高める

- リピーターを増やす

- 顧客の満足度を上げる

→ すべては利益のために、顧客の行動に影響を与える

→ ユーザーエンゲージメント

ここで注目すべきなのは、「ユーザーが何かを学ぶ」という視点がこの仕組みに含まれていないという点です。

実際、Redditには「連続ログイン記録(streak)」を維持するためだけにアプリを開いているという投稿が多数あります (1、2、3)。つまり、学習そのものよりも streak を維持することが目的化しているのです。もちろん、「streak のためにアプリを開くということは、多少なりとも言語学習につながっているのでは?」という見方もあるでしょう。しかし、アプリを開く動機が学習ではなく streak の維持であるという事実は、深刻な問題をはらんでいます。

さらに深刻なのは、streak を失った瞬間にモチベーションが一気に低下し、アプリの使用自体をやめてしまうというケースが多いことです(Reddit 参照)。それでは、そもそも彼らの「学習への動機」はどこにあったのでしょうか?

ここで重要なのは、Nicholson(2012)、Pink(2009)、Deci(1971)といった研究者たちが述べているように、要点をまとめれば:

報酬を取り除けば、行動も消える

ということです。

このような傾向が、ユーザーが自らアプリをダウンロードし、ある程度自律的に利用しているところで起きているのであれば、果たして、学校などの教育現場で外発的な報酬で学習行動をコントロールしようとしたとき、どのような結果を招くのでしょうか?

本稿では、教育現場におけるゲーミフィケーションの問題点を指摘し、「遊び心(ludic)」を基盤とした、より人間的な教育の在り方を提案します。

ゲーミフィケーションの問題点

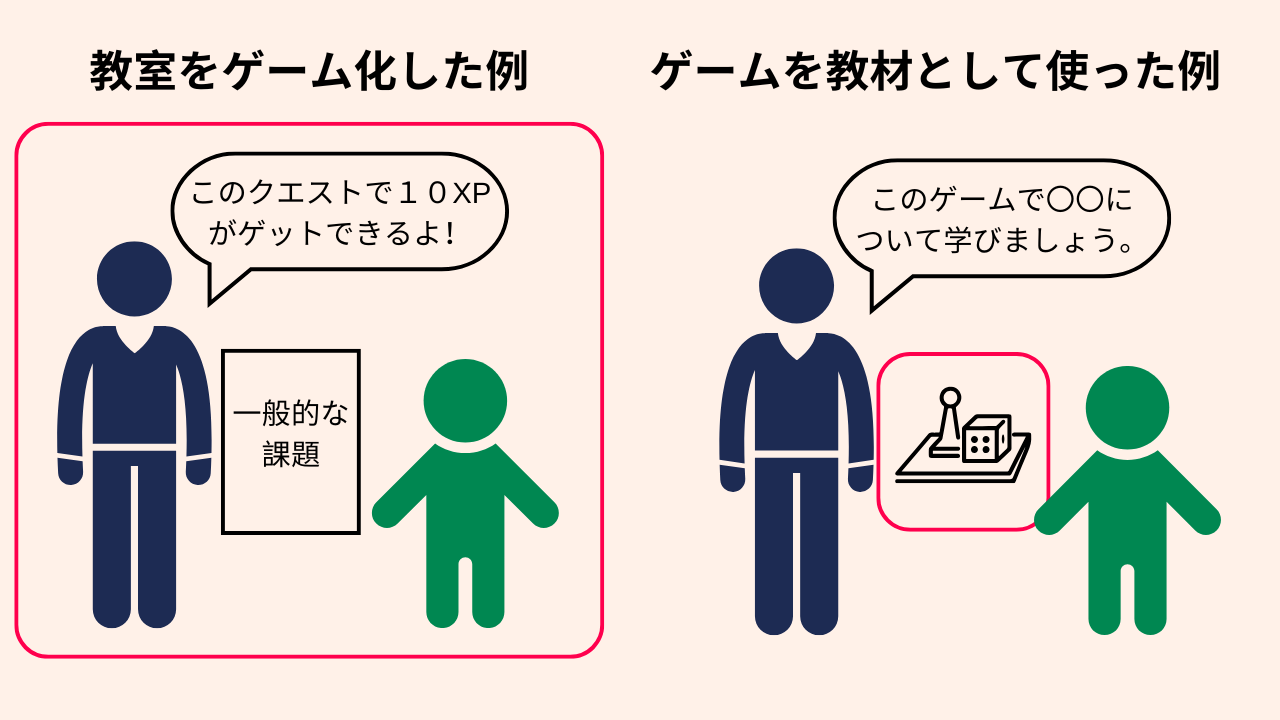

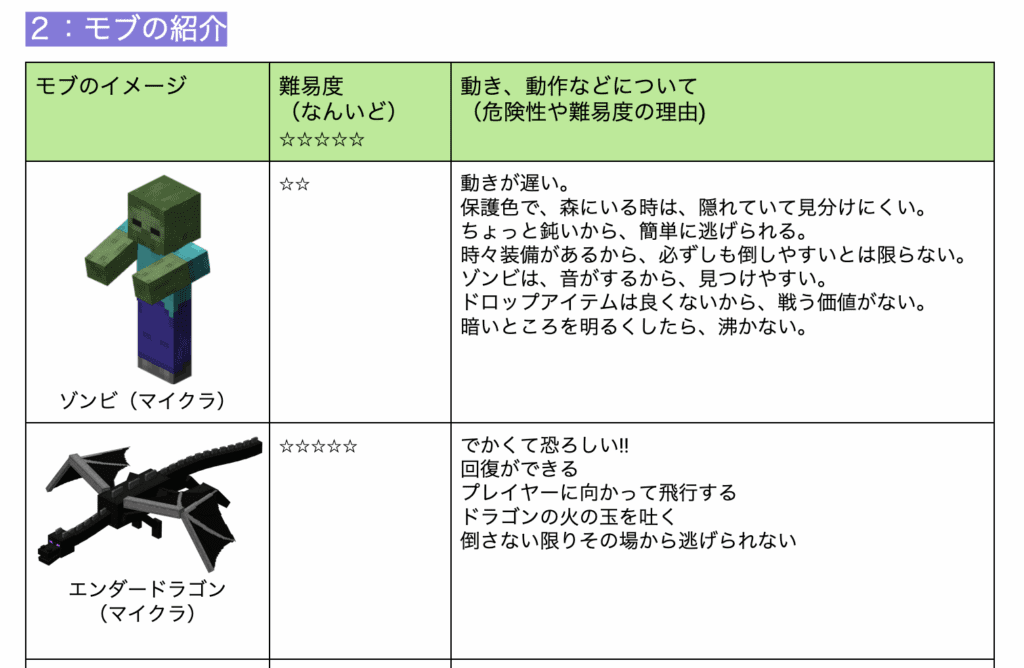

教育構造を変えない表層的アプローチ

ゲーミフィケーションは、教育の仕組みそのもの(たとえば成績のつけ方、出席のルール、課題中心の学び方)を変えるのではなく、その外側に「ポイント」「バッジ」「ランキング」などの飾りをつけるだけの方法です。これにより、学生は行動を操作される対象となり、教師は単なる管理者としての役割にとどまります。つまり、教育における人間関係や動機づけの根本にアプローチするものではありません。

ゲーム研究者のイアン・ボゴスト(2014)は、ゲーミフィケーションを「ダッシュボード化(dashboardification)」と呼び、それはゲームとはまったく別物であり、見た目だけゲーム風にして、数値化や管理の道具として使っているにすぎないと指摘しています。そこには、本来のゲームに見られる「選択」「葛藤」「意味のある活動」は存在しません。

ちなみに、私はダッシュボードの仕組み自体が悪いものだとか、教育現場に導入すべきでないとは思っていません。学生が自分の進歩を確認できるフィードバックや成果の測定は必要です。 ただし、それはゲーム本来の要素とは無関係であり、「ゲームを参考にした学び方」として強調するものではないでしょう。 また、ダッシュボードを導入したからといって、それだけで教育的に価値のあるものを提供しているとは言えません。たとえ評価基準やフィードバックが整っていても、授業やカリキュラムの内容、そして学習方法(pedagogical approach)が同じくらい重要だからです。

競争を助長し、他者と比較させる設計

ゲーミフィケーションの多くは、競争を前提としています。ポイントやランキングがその象徴です。しかし、このような外的動機づけ(extrinsic motivation)は、一部の学生には効果があっても、多くの学生にとっては「疲れる」「追いつけない」「やる気が削がれる」体験になります。特に教育の場では、比較や競争ではなく、内発的な学びや安心できる空間の提供こそが求められます。

生徒はすぐに見抜く:「これ、ゲームじゃないでしょ」

教師が「楽しいゲームを用意しました!」と意気込んでも、それが単なる課題+ポイント制の「ごっこ遊び」であれば、生徒はすぐにその仕掛けを見抜きます。むしろ信頼関係を損ない、学びそのものへのモチベーションを下げてしまうリスクもあります。

「ゲーミフィケーションの6要素」はただの「良い教育」では?

日本ゲーミフィケーション協会(JGamifa)は、以下のような「ゲーミフィケーションデザイン6要素」を提示しています(出典):

- 能動的な参加(たのしそう → 参加したい)

- 達成可能な目標設定(できそう)

- 称賛を演出(ほめられる)

- 即時のフィードバック(すぐに反応がある)

- 成長の可視化(だんだんできるようになる)

- 独自性の歓迎(工夫して良い)

一見すると魅力的な要素に思えるかもしれませんが、これらはすべてゲームに特有の設計ではありません。むしろ、すべての良質な授業や教育が備えるべき基本的な教育原則です。つまり、教師が日々自然に心がけていることを「ゲーミフィケーション」と再定義しているだけであり、Bogostの批判のように、これらはゲームの要素とは言えません。

本来の意味におけるゲーミフィケーションは、もっと限定的な概念です。これらの教育的な良い実践を「ゲーム的だから良い」と誤認することは、ゲームという文化的形式の誤解につながり、同時に教育実践の本質的価値も歪めかねません。

ケーススタディ:プログラミング不登校生徒へのアプローチ

以下のような「ゲーミフィケーション」のアイデアが紹介されていました。

- 教室に来たら1pt

- 雨の日に来たら+1pt

- 友達にアドバイスして喜ばれたら2pt

- プログラミング作品を公開したら1pt

- いいねの数だけpt

- アルトークンがもらえる!

これは、単なる「成績評価の変形」であり、ゲームでもなければ、学びの意味を変えるような仕組みでもありません。ポイントを付与したからといって、不登校の背景にある社会的・心理的・制度的な課題が解決されることはありません。本来であれば、その生徒自身と保護者に向き合い、なぜ登校できないのか、何が障壁となっているのかを丁寧に聞くべきです。

代替案:ルディック(ludic)な教育

私は、「遊び心」を中核に据えたルディックな教育を提案します。これは、以下の2つの要素を活かすアプローチです。

- ルディック・オブジェクト(ludic objects):遊びを意図して設計された教材やツール(ゲームがその一部)

- ルディック・プラクティス(ludic practices):教師自身の遊び心、柔軟な授業設計、意図的な余白の活用、学習法、など

このアプローチでは、教師が持っている素材や状況の制約の中で、「どこに遊びの余地をつくれるか?」を問い直します。つまり、授業に遊び場(playground)をつくり、学生が自由に探求できるようにするのです。ポイントではなく、「意味のある選択肢」や「想像力を引き出す問い」によって学生の内発的な動機を刺激します。

Ludic Objectsについて

私は「ゲーム」ではなく「ルーディック・オブジェクト(ludic objects)」という言葉を使います。これは、より広く包括的な表現だからです。「遊戯的」(ルーディック)はデジタル・アナログのゲームだけでなく、物語作り、ロールプレイ、シミュレーションのような遊びの活動も含みます。これにより、特定の技術やゲームの種類に限られない、多様な遊びの教育実践を探求し共有することができます。例としては、以下のものがあります。

- ディベート

- デジタルゲーム

- 演劇(ドラマ)

- 言葉遊び(ユーモア、ジョーク、詩、なぞなぞなど)

- ライブアクション・ロールプレイングゲーム

- ごっこ遊び

- 遊び心のあるワークシート、アクティビティ、カリキュラムなど

- シミュレーションとロールプレイ

- 物語づくり(ストーリーテリング)

- 卓上ゲーム(テーブルトップゲーム)

- 伝統的な遊び(さいころ遊び、会話遊び、校庭の遊びなど)

具体例

Ludic Practice 1: プロゲーマー的評価基準

自分のやったことの中で例をあげると、プロゲーマーが作成するモンタージュ動画に着想で、学生がグループワーク中の「一番いいパフォーマンス」を提出するポートフォリオ評価を導入しました。もっと具体的に言えば、これは「英語コミュニケーション」の授業の中で導入したし、年度によれば、学生がGoogleドキュメントで提出したり、動画を取って提出した場合もあります。その一例が以下の動画です。あと、そうですね。この授業は「ゲームを使って英語コミュニケーションを身につける」をテームにしたものでピュアにゲーム学習というものでもあります。ただ、そこにフォーカスしなくてもいいです。評価の仕方が私なりの「ゲームを参考にした学び方」です(はい、嫌でも私が「ゲーミフィケーションをやっている」と言えません)。

「ゲーム要素」そのものではありませんが、ゲーム文化やその関連実践に影響を受けた評価基準です (York, 2023)。

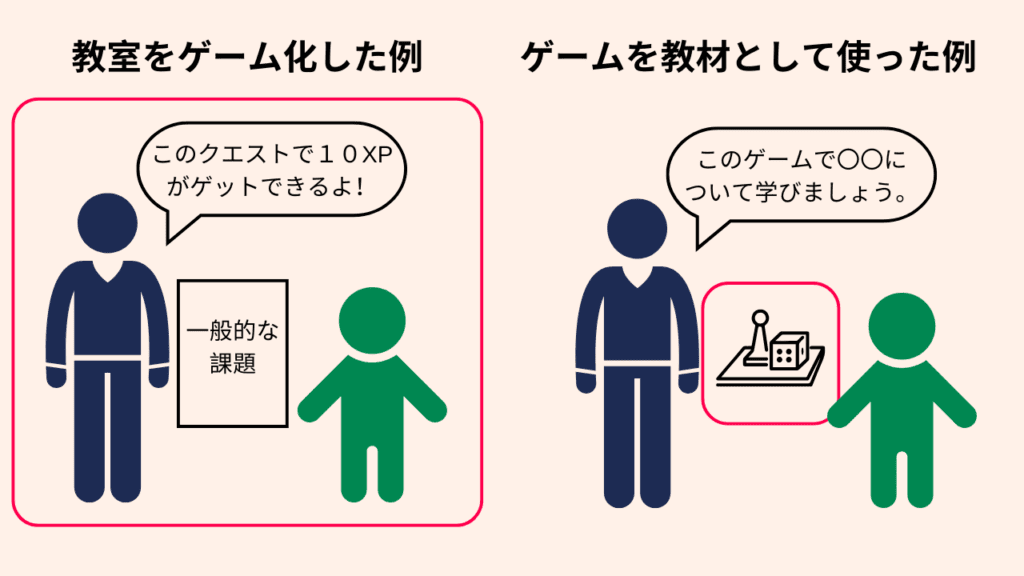

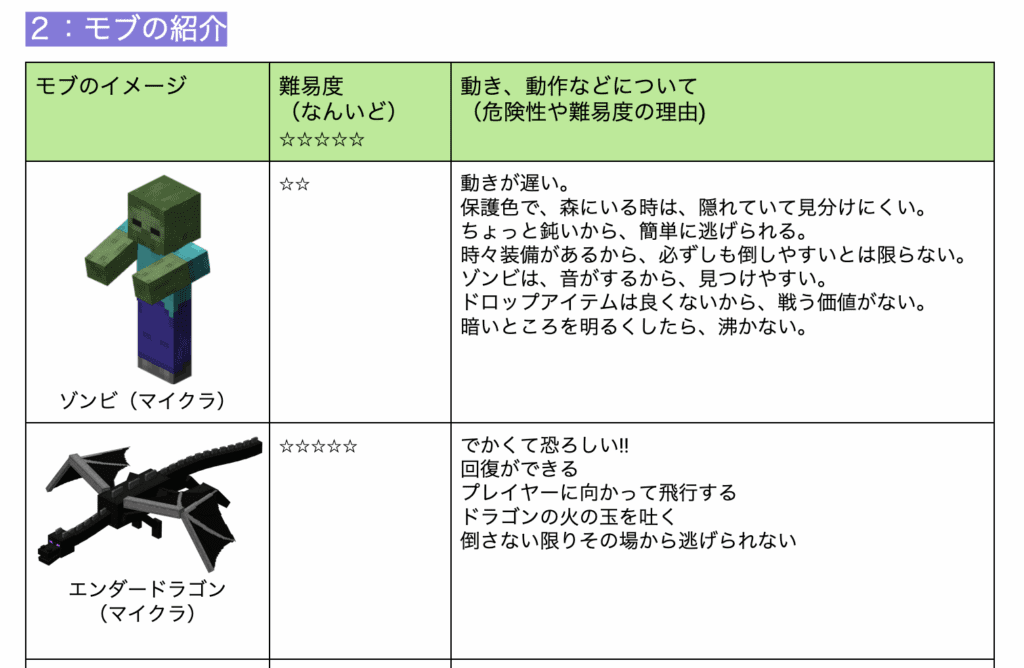

Ludic Practice 2: マイクラを使った日本語の比較級を学ぶ

世界中の人々に日本語を教えています。Minecraftを舞台として授業を行ったり、活動をしています。しかし、Minecraftを現場の教室に取り入れるのは難しいことを十分に理解しています。そのため、実験として、ゲーム自体を使用するのではなく、ゲームからのキャラクターやモブをもとにした比較が学べるレッスンプランを作成しました。学生はMinecraftのモブをリストアップし、それらの特徴について書いた後、強さの観点から比較しました。

以下に、この活動を模倣したい場合のために、(完成した)ワークシートへのリンクがあります。

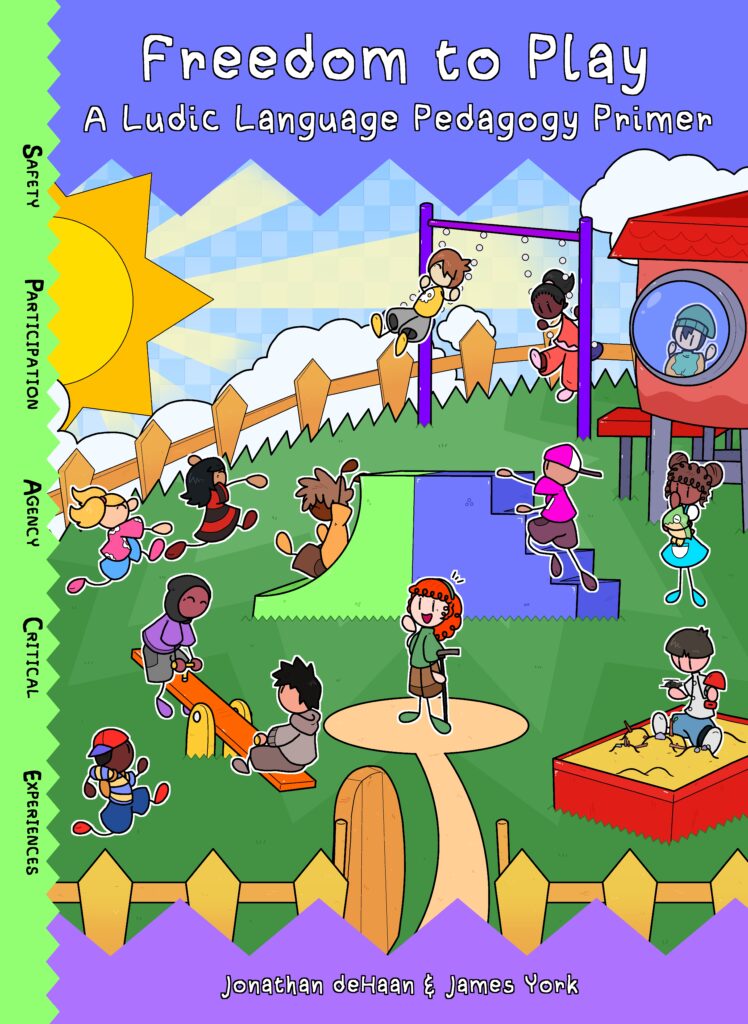

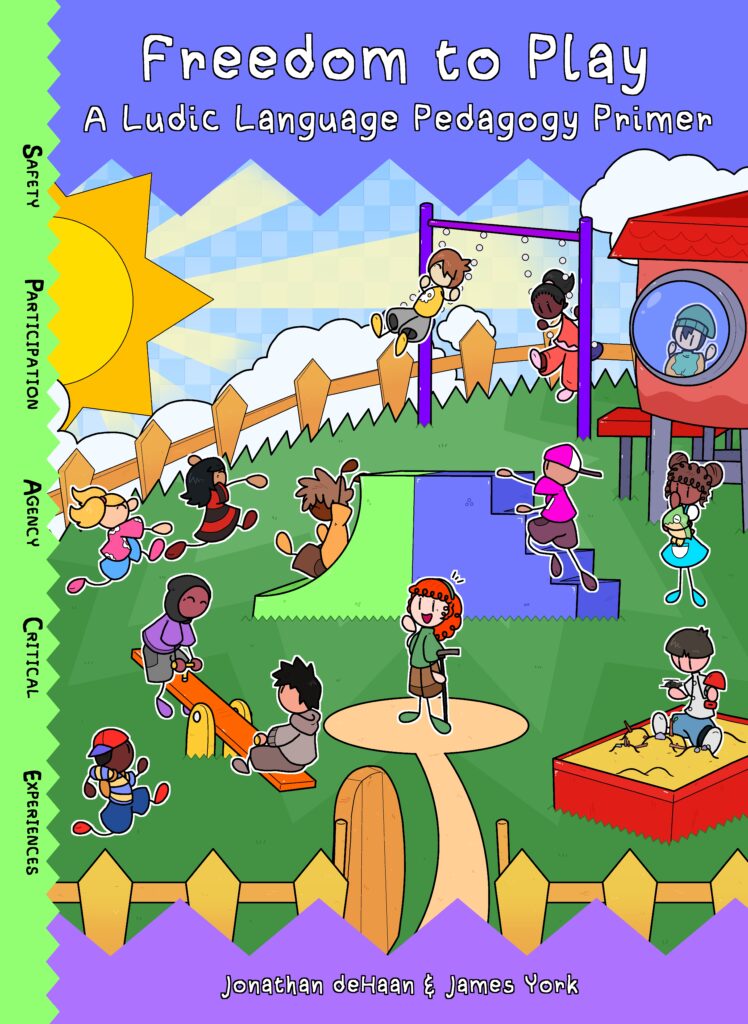

もっと事例を聞いてみたいですか?

最近、ジョナサン・デハーンと共著で出版した本には、同じような例がいっぱいあります(deHaan & York, 2025)。ぜひとも見てみてください!

English version

Introduction

Here is the English translation in your academic voice:

In educational settings, the term “gamification” is still frequently used as something of a buzzword. This is likely because implementing gamification is seen as an easier alternative to fundamentally rethinking course content, pedagogy, or the nature of education itself.

In fact, I was also drawn to its potential around 2012 and attempted to implement gamification in my own classes (York, 2012). I allowed students to choose from a range of tasks and complete them in a way that suited their own learning styles. However, rather than boosting motivation, the result was that students overwhelmingly selected only the simplest tasks. In other words, they avoided more challenging assignments altogether.

This kind of behavior is a well-documented side effect of extrinsic rewards (Hashiguchi, 1982). When the desire to avoid losing a reward becomes strong, learners tend to avoid the risk of failure by choosing safe, easy tasks that guarantee a payoff. In this way, while gamification may appear effective on the surface, it can in fact lead to unintended consequences in learner behavior. In this article, I want to introduce the idea of “playful” or “ludic” education is what we need. Not gamification. I’ll also introduce some examples of how this can be done.

Duolingo

Before we even step into the classroom, the first app that comes to mind when we talk about gamification is probably Duolingo. It’s often described as a service that “incorporates game-like elements.” But can we really call this a game? And does introducing these kinds of services into education truly improve the quality of learning?

Recently, Duolingo has come under heavy criticism. I believe that at the heart of this is the structure of gamification itself. The raison d’être of gamification is to control and manipulate user behavior, typically for purposes like:

- attracting more users

- increasing repeat engagement

- boosting customer satisfaction

→ all ultimately to influence behavior for profit

→ user engagement

What’s important to note here is that helping users learn something isn’t built into this structure at all.

In fact, Reddit is full of posts from people who admit they open the app just to maintain their streak (see: 1, 2, 3). In other words, keeping up the streak becomes the goal itself, rather than the learning. Sure, one might argue: “Well, if they’re opening the app for the streak, isn’t that at least contributing to some language learning?” But the fact that their motivation for opening the app is streak maintenance, not learning, points to a serious issue.

What’s even more problematic is that once someone loses their streak, their motivation often collapses and they stop using the app altogether (again, see Reddit). So where was their “motivation to learn” in the first place?

As scholars like Nicholson (2012), Pink (2009), and Deci (1971) have argued:

Take away the reward, and the behavior disappears.

If this is what happens when users download an app on their own and engage with it voluntarily, what happens when we try to control learning behavior in schools with extrinsic rewards?

This blog post points out the problems of gamification in educational settings and proposes a more human-centered approach based on playfulness (ludic learning).

The Problems with Gamification

A superficial approach that doesn’t change the structure of education

Gamification doesn’t change the core systems of education (such as grading systems, attendance rules, or assignment-centered learning). Instead, it adds external “decorations” like points, badges, and leaderboards. This turns students into objects of behavioral control, and leaves teachers in the role of managers. It doesn’t get to the heart of human relationships or motivation in education.

Game scholar Ian Bogost (2014) calls this dashboardification — it’s not a game at all, just something that looks game-like on the surface, built for tracking, quantifying, and managing behavior. It leaves out what makes a game a game: choice, conflict, and meaningful activity.

By the way, I don’t think dashboards are inherently bad, nor do I think they shouldn’t be used in education. Students do need feedback and ways to measure their progress. But this has nothing to do with the core elements of games, and I don’t think we should hype it up as “game-inspired learning.” And just having a dashboard doesn’t mean you’re offering something educationally meaningful. Even if you have clear criteria and feedback, what really matters is the content of the lessons, the curriculum, and of course, the pedagogical approach.

Encouraging competition and comparison

Many gamification systems are built on competition — points and leaderboards are the clearest example. While this kind of extrinsic motivation might work for some students, for many it’s exhausting, discouraging, or demotivating. Especially in education, what’s needed is not comparison or competition, but spaces where learners feel safe and can pursue intrinsic motivation.

Students can tell: “This isn’t really a game.”

Even if a teacher enthusiastically announces, “We’re going to play a fun game today!” if it’s just an assignment wrapped in a points system, students will see right through it. It can even damage trust and undermine their motivation for learning.

Aren’t the “six elements of gamification” just good teaching?

The Japan Gamification Association (JGamifa) presents these six elements of gamification design:

- Active participation

- Achievable goal-setting

- Praise

- Immediate feedback

- Visible growth

- Welcoming individual creativity

At first glance these might sound appealing, but none of these are unique to games. They’re simply the basics of good teaching. In that sense, “gamification” is just a rebranding of what good teachers already strive to do. As Bogost argued, this has nothing to do with what makes games special.

In fact, gamification as it is actually implemented is a much narrower concept. Confusing good educational practice for “game-like” practice risks both misunderstanding games as a cultural form, and distorting the real value of educational work.

Case Study: A gamification approach for a programming class with absentee students

Here’s an example that was shared as a “gamification” idea (where the students are not turning up for classes for some reason).

- 1pt for showing up

- +1pt for showing up on a rainy day

- 2pt for helping a friend and making them happy

- 1pt for publishing a programming project

- points equal to the number of likes they get

> They could earn “alt-tokens” this way!

But this is just an alternate form of grading. It’s not a game, and it doesn’t create meaningful change in learning. Simply giving out points won’t solve the social, psychological, or systemic issues behind absenteeism. What’s really needed is listening carefully to the student and their family — understanding why they can’t attend and what barriers they’re facing.

A better alternative: Toward ludic pedgogy

I propose an approach centered on playfulness — what I call ludic pedagogy. This draws on two key elements:

- Ludic objects: materials or tools designed with play in mind (games are part of this)

- Ludic practices: the teacher’s own playfulness, flexible lesson design, intentional openness, creative pedagogy

This approach invites teachers to ask: Where can I create room for play within the constraints of my materials and setting? The idea is to build a playground within your lessons where students can freely explore. Rather than points, what motivates learners are meaningful choices and questions that spark imagination.

About Ludic Objects

I use the term ludic objects rather than just “games” because it’s a broader, more inclusive expression. Ludic includes not only digital and analog games, but also activities like storytelling, roleplay, and simulation. This lets us explore and share diverse educational practices without being limited to specific technologies or types of games.

Examples include:

- Debate

- Digital games

- Drama

- Language play (humor, jokes, poems, riddles, etc.)

- Live-action role-playing games

- Make-believe

- Playful worksheets, activities, and curricula

- Simulations and roleplays

- Storytelling

- Tabletop games

- Traditional games (dice games, conversation games, playground games, etc.)

Examples of ludic practice

Ludic Practice 1: Pro-gamer inspired assessment

In my own work, I created a portfolio assessment inspired by pro-gamers’ montage videos. Students submitted their “best performance” from group work. This was part of an English communication class, and depending on the year, students submitted Google Docs or videos. (One example video is linked below.) The course itself focused on learning English through games, but that’s not really the point — the assessment was my way of drawing on gaming culture for learning. (So no, I wouldn’t call this “gamification.”)

This wasn’t a “game element” itself, but an assessment influenced by gaming culture and its practices (York, 2023).

Ludic Practice 2: Learning Japanese comparatives using Minecraft

I teach Japanese to learners around the world. I’ve run lessons and activities using Minecraft as a setting. I also understand how hard it can be to bring Minecraft directly into a classroom. So as an experiment, I designed a lesson that didn’t use the game itself, but drew on its characters and mobs. Students listed Minecraft mobs, described their features, and then compared their strengths using comparatives.

Want more examples?

Our recent book (Freedom to Play, deHaan & York, 2025) is full of ideas like these. Please check it out!

参考文献 — References

- Bogost, I. (2014). Why Gamification is Bullshit. In Walz, S.P. & Deterding, S. (Eds.), The Gameful World: Approaches, Issues, Applications. MIT Press.

- Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030644

- deHaan, J. & York, J. (2025) Freedom to play: A ludic language pedagogy primer. Peter Lang, New York. https://www.peterlang.com/document/1363760

- Nicholson, S. (2015). A RECIPE for Meaningful Gamification. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (Eds.), Gamification in Education and Business (pp. 1–20). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_1

- Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

- York, J. (2012) English Quest: Implementing game mechanics in a university EFL classroom. Modern English Teacher 21(4), 20-25.

- York, J. (2023). Pro-Gamer Inspired Speaking Assessment. In S. W. Chong & H. Reinders (Eds.), Innovation in Learning-Oriented Language Assessment (pp. 257–275). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18950-0_15

- 橋口捷久. (1982). 内発的に動機づけられた行動の規定因としての外発的報酬と達成関連動機. The Japanese journal of psychology, 53(5), 281–287. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.53.281

- 日本ゲーミフィケーション協会. (2022). 「教育×ゲーミフィケーションの魅力と事例」 デジハリ大学院 特別授業

Leave a Reply